A couple of newsletters ago, I wrote about the stress I was feeling as PhD decisions were set to start trickling out in two weeks. Well, it’s two weeks later, and decisions are coming out any day now. I am, as you can imagine, even more stressed now about the application process.

In times like these, I have a few requirements for the food I eat. One, a dish should be comforting: I tend to like something warm and rich. Two, it should be nourishing and vaguely nutrient-dense. And three, it needs to be extremely easy to make, as when I am stressed, I have difficulty motivating myself to follow complicated recipes with tons of steps.

These days, only one thing seems to fit the bill, so I find myself eating a lot of savory oatmeal. I got a big bag of local Purple Mountain Grown oats at the Dupont Circle Farmer’s Market, and I cook them for about 15 minutes with bone broth made from Ecofriendly Farm’s beef knuckle and marrow. I stir in a whole lotta kale, chili oil, and, lately, urad dal miso made by my wonderful friend Rohan (maybe if we are lucky he will drop the instructions to make it on his substack). It is creamy, wholesome, and unctuous. I hope you try it, and that it soothes your nerves and stomach as much as it soothes mine.

We don’t usually think of the word “farmer” as having a complex definition. After all, a school-aged child could ostensibly define it. But the profession of “farmer,” at least in the United States, is consistently misdefined in popular discourse. As agricultural historian Gabriel Rosenberg argued in a recent essay, most people using the word farmer treat it as a category of labor rather than a property relation. But, Rosenberg argues, this is not correct: farmers are “people who own businesses that generate revenue from the production and sale of agricultural commodities.” We should not collapse “farmer” with “agricultural worker” or “farmhand.”

This is more than a mere semantic quibble. Most farmers in the US, Rosenberg writes, “have class interests that don’t align with workers,” preferring “lower wages, weak environmental and labor protections, lower taxation, and fewer social welfare programs.” And yet, farmers maintain a “yeoman pastoral image” in the public eye, which effectively curbs public demands to regulate most forms of agriculture. As a recent piece in The New Republic written by Rosenberg and Jan Dutkiewicz point out, the general US populace is banned from treating animals cruelly, discarding debris in open waterways, firing workers for joining unions, and employing children younger than 14 years old. The exception to these rules are farmers, who for the most part are “older, rich, white people with conservative political beliefs.” (This, of course, is by design: historian Pete Daniel has detailed how between 1940 and 1974, the levels of Black farmers in the US dropped by 93% due to systemic oppression by the US government.)

This is not to castigate present-day farmers or to say that farmers do not labor on their land or produce food for subsistence. They can and do. And this definition of farmer does not necessarily hold true for countries in the Global South, which can have different land-tenure laws and levels of subsistence agriculture practiced. But, we cannot keep equating farmers in the US simply with those who labor on farms: as Rosenberg cautions, “until we move away from a system of land tenure rooted in real property rights, I see no other way to make sense of the incentives that drive behavior in American agriculture.”

Other food-related pieces occupying my mind:

Speaking of farmers in the Global South, Civil Eats recently published an op-ed on the past—and future—of the farmer’s movement in India. Just because the farmers won in their 2020-2021 protests against the Modi government’s farm laws which, among other things, would have effectively curtailed legal recourse available to farmers does not mean the fight against big agribusiness in South Asia is over.

The links between food systems and the prison industrial complex run deep. I really appreciated this interview by anthropologist Ashanté Reese with five activists working at the intersection of carcerality and food (side note: if you have not read Dr. Reese’s monograph Black Food Geographies, I really recommend checking it out).

Has anyone else noticed that the food in Succession looks absolutely disgusting? Well, The Cut did, and they rounded up some of the most revolting dishes featured in the show.

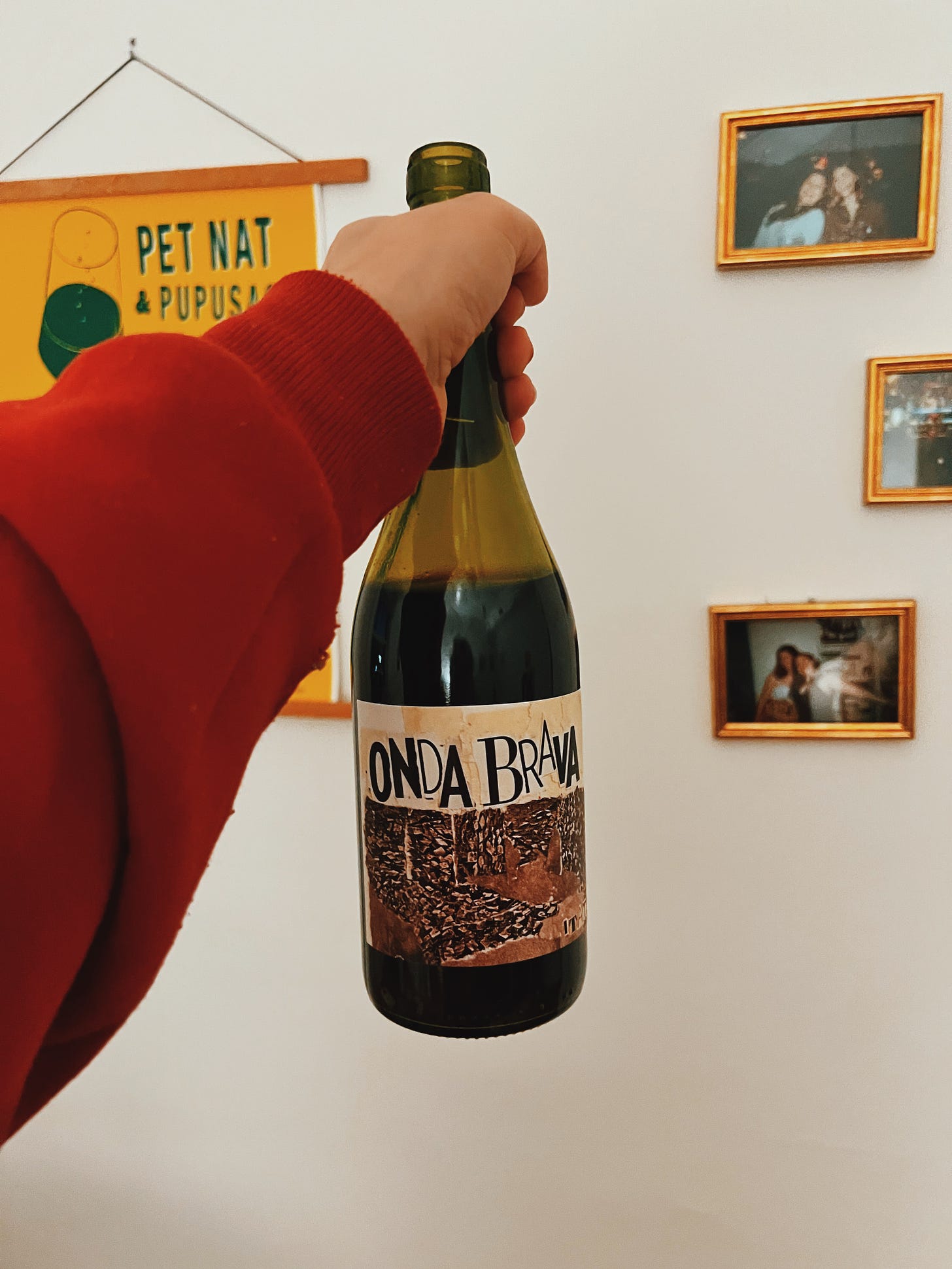

This week, we opened up a bottle of a 2019 cinsault produced by Onda Brava in Itata (which is often deemed the birthplace of wine in Chile). As I learned through my Children’s Atlas of Wine class, it is made half via foot-stomping and half via zarandas, or bamboo rollers.

The overwhelming note on this wine for me was cherry, but not in a medicinal or saccharine way. Rather, the fruitiness was followed up by a lovely whiff of pepper and herbs. This would be a good wine with a nice full-bodied winter stew (or savory oats).

Here is a brief update on some of the food-related work I’ve been engaging in lately:

Nothing. I am just checking GradCafe obsessively over and over again.

Just kidding! (Well, kind of). This week, I finally finished the first draft of my narrative on maize for the Plant Humanities Lab. I was lucky that Helen Curry’s excellent new book on transgenic maize came out before my piece was due. Here is a great summary of some of her findings.

I’m also gearing up to pitch a new piece based on some of my research on catawba wine… hopefully more updates to come. Stay tuned!

Thanks for reading! I hope this week brings auspicious news for all of us, and that we fill our stomachs with something delicious. If I’m feeling up to it, I might even branch out slightly from my usual savory oatmeal and make this instant pot chicken juk by Kay Chun.

Love, Julia